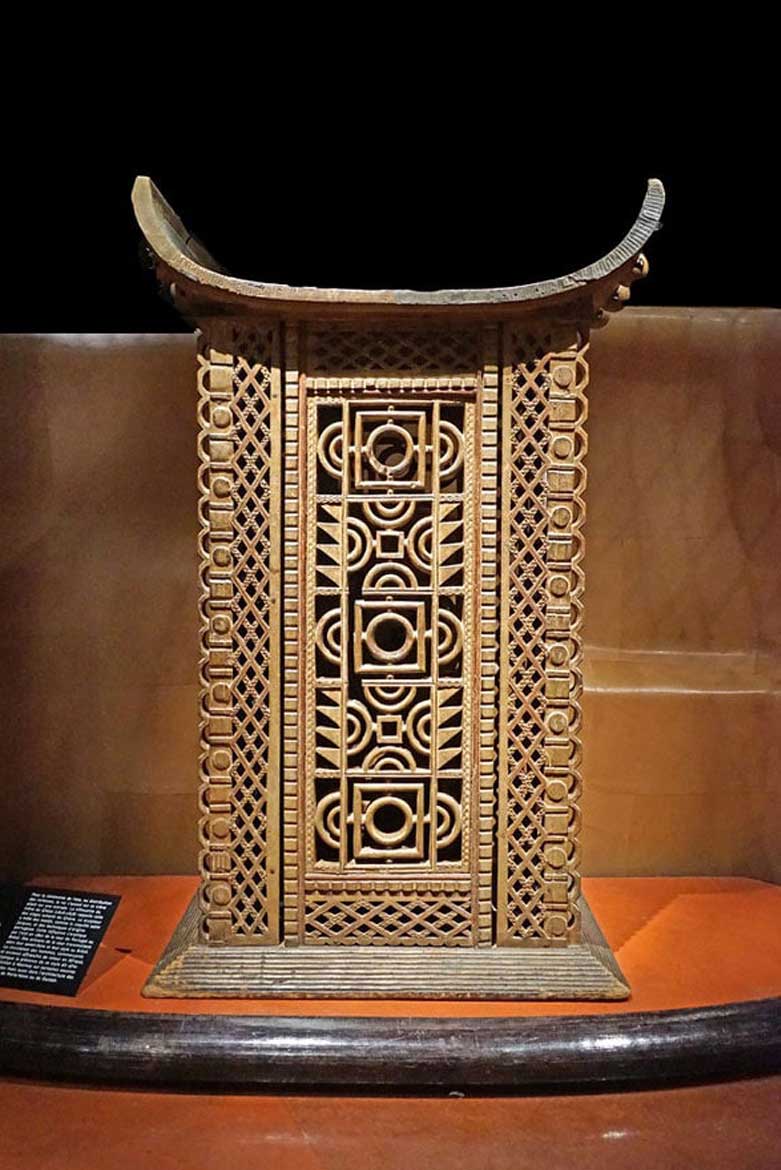

On Tuesday, November 9, 2021, France officially returned to Benin some 26 works of the royal treasures of Abomey from its spoils of war after the conquest of the Kingdom of Danxomè (Dahomey) by General Alfred Dodds in 1892. This is a first step, and there is no reason that the other objects stamped "spoils of war" should not be returned.

This first step was only possible thanks to an exceptional law voted in December 2020 and which allowed an exceptional derogation from the principle of "inalienability" of works in French public collections, in that these were the object of characterized looting. However, the restitution made by the French State of the works in question to the State of Benin is neither the first vis-à-vis an African State. Even if it is part of a dynamic favored by a desire on both sides of the Atlantic to ease the tension of a painful but no less indelible history inherent in slavery and the colonization of the peoples of Black Africa specifically.

“Africa needs this self-knowledge. It must redefine itself around this heritage which until now has been too inaccessible to it", declared the businessman of Congolese origin, Sindika Dokolo, and also husband of Isabelle dos Santos, the daughter of former Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos. Probity would like us to recognize that he was the first in Africa to work since 2015 for the restitution of works stolen from Africa. Thanks to the Sindika Dokolo Foundation that he created, he thus succeeded on Thursday, June 7, 2018 in Brussels in having treasures officially returned to the Angolan government, represented by its Ambassador in Belgium and by the Director of the National Archives. Which consisted of two masks, a chair, a stool, a pipe and a cup of Chokwe or Shinji invoice which found their places within the national collections of the Museum of Dundo, from where they had been stolen during the Angolan civil war , then resold in Europe.

Towards the end of February 2020, Sirak Asfaw, a former Ethiopian refugee in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, presented Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed with an 18th century crown that he had hidden for more than 20 years in his apartment, after have taken possession. Thanks to the help of a Dutch art expert, Arthus Brandla and the unheralded mobilization of the Dutch government. Said crown made with engravings representing Jesus Christ and his apostles and decorated with gilded copper, was the property of Ras Welde Sellase, one of the most powerful Ethiopian warlords of the 18th century who had offered it to a Church not far from the city of Mekele, in the north of the country.

The brilliant and extraordinary Kingdom of Benin, located in present-day Nigeria, saw thousands of its metal and ivory carvings looted by British forces in 1897 during the sack of Benin-City, the capital of said Kingdom. Some of them then disappeared into numerous private collections, after they were put up for auction in the United Kingdom. Thus one of the sculptures representing the bronze head of an Oba (King) sold in 1957 to the University of Aberdeen was returned to Nigeria. “It would not have been fair to keep an object of such cultural significance that was acquired under such reprehensible circumstances. We therefore decided that an unconditional return was the most appropriate measure,” said Professor George Boyne, President of the University of Aberdeen.

According to specialists, nearly 85% to 90% of African heritage works of art still remain outside the continent and mainly in the public collections of the former colonial powers. A situation that has created a continent-wide return movement since 2019, and which has already seen several masterpieces return to Africa. This is the case of Nigeria. Apart from Benin, several other countries on the continent have officially made requests for restitution, such as Senegal, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Chad, Mali, Madagascar, to name but a few.

Black Africa must look to the future by striving, as much as possible through dialogue, to recover its heritage once stolen by those who, however, never ceased to look at the cultures to which all these treasures belonged, some of which were occasionally exceptional class masterpieces. It is certainly very commendable to fight in order to recover all the treasures that have been stolen from the African continent. It would still be necessary to safeguard what is in danger and which requires more urgent efforts to preserve it for future generations. This is the case for example - among many others in danger - of the Datawory Site, the last witness of one of the longest African resistance led by Kaba in the Atacora department, in the North-West of Benin. Apart from its exceptional historical value on the history of colonization in Benin and West Africa, the site should have been an archaeological excavation site for many years.

Unfortunately, nothing happened and the deterioration continues. When here and there in Africa many tourist or historical sites are exposed for years to bad weather and looting by the first comer, one is entitled to wonder if the objective of this movement of returning looted treasures to Black Africa does not have a much more symbolic and eminently political character than that of a real awareness of the importance of its heritage and the urgency of caring about it, saving it, and above all promoting it. .

History is not rewritten, it is written, once, and once and for all. And once it is written, it can be falsified, corrected, concealed or more or less taken into account. It depends ! But anyway, what happened happened. And past time never comes back, at least not in exactly the same way in the same space-time frame. It is the essence of all existence. Nothing can be done about it. No one can change their past. Only on the future, we can act. And this is the most important issue for the protagonists of the past or the present who can potentially be artisans of the future. Black Africa must now know how to look its History in the face: dust it off from untruths and other misinterpretations dating from the colonial era and not rewrite it by complacently embellishing it. But alas, there are not many States that have already tackled this task, which is clearly worth it. That's the least we can say.

By Marcus Boni Teiga