Invoking history is always compelling when couched in fictional narrative the type Nike Campbell has rendered in her recently released novel Saro, an inter-section of family and global historical narrative, published by Narrative Landscape Press, Lagos. In this interview with ANOTE AJELUOROU, Campbell explains her attraction to historical fiction, Saro being her second such effort, and why stories like hers help the Black man, long dehumanised and marginalised, to regain his battered humanity and assume his God-given role of advancing his halted civilisation

What’s your attraction for historical fiction? And why is it so important to you?

I’ve always been fascinated with the past. I grew up in my maternal grandparents’ home, and that probably influenced how I viewed the world. They would tell stories about their lives as youths. Simple lives filled with hope and promise. I would later recreate them in my mind. I also noticed early on that I assimilated and retained more information if I approached it in a less structured and fun way. Historical fiction does that – it educates and entertains. The adaption of several historical fiction to TV series like Game of Thrones and Lord of the Rings, watched by millions around the world and have a cult following, are obvious examples of that.

My approach to almost every situation has always been seeking out the root cause of an issue – why are things the way they are? Why do people act in certain ways? There are reasons for that. History is critical to understanding the present and planning for the future. History sheds light on the causes of the current state of affairs in the world – from politics to economics to religion. We should all be scholars of history.

How does your first historical fiction connect with this new one, and what should readers expect from you next?

Both novels were inspired by family drama. Thread of God Beads’ main character, Amelia was inspired by the life of my maternal great grandmother, a princess of Dahomey Kingdom, who fled during the French-Dahomey war. Saro was inspired by the kidnap of my maternal Grandfather’s forefather, Şiwoolu. I have dabbled into screen writing with two short films under my belt. The stories were adapted from my short story collection Bury Me Come Sunday Afternoon. I’m currently working on a TV series and a contemporary novel which connect the present with the past.

Why did it take you many years to release the second novel?

Life. But really, working a full-time job, raising three children, and pursuing my doctorate degree keeps me busy. Between Thread of Gold Beads and Saro, I published Bury Me Come Sunday Afternoon, a collection of short stories, and adapted two of the short stories – Losing My Religion and Apartment 24 – in the book into short films. Both films were screened at an international film festival and are currently on Amazon Prime video platform. Abeokuta’s history will not be complete without a mention of the infamous slave trade and the returnees, the Saros.

How much does the city under the rock owe these returnees?

I have a different opinion. There are no victors in this horrible inhumane activity that has impacted the globe. Many participated in the business of slave trade, but many also did not. Madame Tinubu is a character in Saro. Her role in the novel as a slave trader was necessary to acknowledge rumours of her involvement. She was a philanthropist, but she is also known to have been a slave trader. She represents so many others in Abeokuta and beyond who were in cohorts with foreigners to profit off the lives of our people. But to say that the city itself owes the returnees is akin to sentencing everyone for the crimes of a few.

Of course, your mother kept a record that probably set you off. But how much research other than her record did you carry out to realise this fictional Saro narrative?

Quite a lot. I read several history books on Abeokuta and how it was formed, and conducted numerous online research that informed my writing of that period. It’s amazing how the research led to revelations – the ripple effects of the slave trade and how the Yoruba culture has been transported to numerous countries and is evident in the culture and religions. Centuries of slavery and subjugation could not kill the beliefs and traditions.

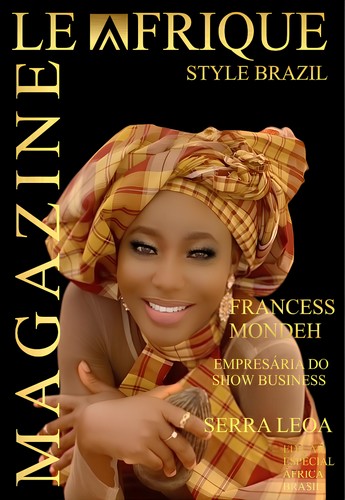

I travelled to Sierra Leone to get a firsthand experience of the place and the people, and what a world of difference. Freetown was the home for freed slaves, but there were other sites that existed before the emancipation of slaves. I visited Bunce Island, where slaves were held and sold. This vivid, personal experience made me feel closer to the characters when I wrote about the island. Big Market in Freetown was a place where slaves were also brought for sale. The Cotton tree, where the chained slaves would file past, is still there. I visited Hastings, the community where my characters relocated after their arrival to Sierra Leone. Visiting Fourah Bay College and seeing a huge, framed painting of Bishop Ajayi Crowther trumped it all. Here was a young Yoruba boy stolen away as a slave, and returned to Freetown who, despite his dire circumstances, made something of himself, and then raised others up. I felt so proud standing next to that image of him.

I walked the streets and breathed in the same air that my ancestors had. It was surreal. My experience of Saro was more than just writing a novel; it was finding my roots and digging deep to discover who my ancestors were. I felt a burden to tell their story. Their blood flows through me, and I believe their experiences also shaped who I am.

Set at the tail end of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, Saro dredges up the horrors of that infamous trade. From researching to writing the story itself, what exactly were your emotions?

I can never get over the fact that a human being can sell another. My emotions during the research and writing were raw. They oscillated between pain and anger. Slave trade was not one-sided – Africans also participated. For people to be kidnapped, someone in the community knew the area. It was not some random white man appearing out of nowhere. We (Africans) gave them access and access is power. Unfortunately, we (Africans) still do not realize that once we give access, we have given away our power. It’s the same strategy used to take over native lands from the Native Americans and Indigenous Australians. My emotions were fuel to researching and being as authentic in my writing of the period and the events that occurred then. There have been too many untruths told about that dark era so I had to tell the story from an objective point.

And what part does living in America and seeing African-Americans, offspring of former slaves, have in making this work come alive?

It makes the impact of slavery sink in. I attended Howard University in Washington DC which is a historically black college and university (HBCU). It is a predominantly Black school and one that’s a leading voice for Black representation and social justice. I was immersed in the Black experience and the impacts on Black communities. Not only that, there were calls for action and implementation. I experienced the pride of being Black, and none of the shame that we so often see depicted in movies and media. Over the years, I have continued to see how Black people are marginalised and dehumanised on so many levels, from gerrymandering to racial violence. How much more can a people take? It is not just a physical attack but a psychological one.

If you can make someone believe something about themselves, half the work is done. Although slavery was abolished (we can argue that there is another type of slavery still ongoing – human trafficking), the damage it did to the psyche of African Americans cannot be quantified. The moment is ripe for changing the narrative. Black communities have clued into this and taken their (our) power back. This is evident in the way we embrace the curliness of our hair to the way we dress and talk. We tell our stories. We can no longer rely on the history books written by colonizers. The African proverb still rings true – “Until the lion tells the story, the hunter will always be the hero.”

Your account of Serra Lyoa is so intimate as though you lived there. How did you manage to conjure such warmth in the midst of what was undoubtedly a sorrowful beginning for these people who were stolen from their homes?

I visited the place as I mentioned. The people were so warm and they embraced me for the period of time I was there. I met some people that were so unforgettable that they became characters in Saro. For a family to sojourn in a place for two decades, they must have built meaningful relationships. This was evident in the parent-child relationship formed between Dotunu and Oşuntade, and the one between Şiwoolu and Ajayi Crowther. When we lose something, we often look for it in spaces we find ourselves. Dotunu never knew the love of a mother, but she found one in Oşuntade. Şiwoolu lost his father in the most horrific way, and he found solace in his talks with Ajayi Crowther. This is much the same with us. We seek to fill a void in our lives consciously or unconsciously.

In Serra Lyoa, Siwoolu is eager to shed his African traditions – part of his princely heritage – to embrace the white man’s religion. Are you surprised that the vast majority in Abeokuta and indeed the entire country Nigeria have also abandoned the faith of their fathers for imported ones?

I think our colonisers did a pretty good job convincing us to shed almost everything that made us unique, including relinquishing our African traditions. Our identity was stripped away. The missionaries brought religion to Abeokuta, but they were only a front for the British establishment to seize the wealth. It’s not just Abeokuta, but most of Africa that has abandoned African traditions. I’m not against Christianity, I am a Christian, but with anything, don’t accept everything without questioning. I see the introduction of Christianity into Africa as a tool our colonizers used successfully to gain access and the missionaries were their emissaries. Once they established trust and gained access, they won. We shouldn’t completely abandon our African traditions, but rather research and determine what is beneficial to hold on to.

Do you fear that some aspects of your historical narration could be challenged, especially the crowning of the Alake of Egba with commonly held accounts among the people on what could be the true rendering of events?

This is historical fiction. Of course, it can be challenged, but it is still fiction. It’s not a memoir or biography. I included as much information as I could based on research and our family’s oral tradition, as well as my personal experiences as a child visiting Ake. I do enjoy passionate and respectful discourse, so I welcome discussions about Saro and events in the book.

At what point do the historical and fictional narratives collide and depart?

Interesting question. If you are referring to the main characters that were inspired by real people, they are Şiwoolu, Dotunu, and their children. These were my ancestors – the Coker family. Of course, Bishop Ajayi Crowther and Madame Tinubu were people that existed, and were written into the story. I reimagined Bishop Ajayi Crowther as having close ties to the family during the time they lived in Sierra Leone. In the case of Madame Tinubu, her possible involvement in the slave trade would have had an impact directly or indirectly on the kidnapping of Şiwoolu and Dotunu. The other characters were imagined, one actually inspired by a person I met in Sierra Leone on my visit. His name was Calypso. In his younger days, he was a travelling dancer throughout Sierra Leone. Waltz, one of the supporting characters, was forged from Calypso’s interesting life.

By Anote Ajeluorou

Source: https://guardian.ng

The Guardian (NIGERIA)