In a recent article Professor Grégoire Biyogo raised the following intriguing question: “When does one become philosopher or Egyptologist». We seize the opportunity of Biyogo’s concern to bring to the fore this question on our own area of theological investigation. Biyogo, indeed alerts against the risk of mixing artificially things which normally cannot be put together. As a matter of fact, he reminds us that the danger is huge to make such mixture in the context of the formal definition of our crucial objectives. What is more, provided that we are committed in a venture of research, the social and political targets of which challenge the sense of history, such a questioning cannot be avoided.

As announced earlier, Biyogo’s question amounts to asking ourselves: “When does one become a theologian?” This question had been at the heart of hot debates by the time when African theology emerged. It still comes back into discussion among young scholars in search for some initiation to African theology.

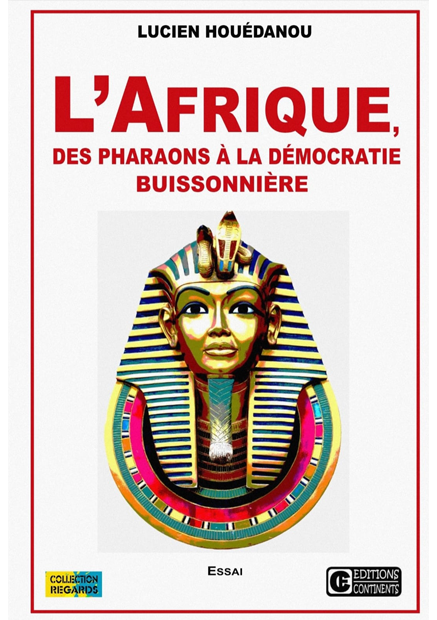

In what follows we take the question up at this decisive time as we are striving to set up our project of writing a history of African theology from the pre-dynastic period up to our days. However, it appears first of all necessary to depict in clear terms what theology actually is.

Derived from a literal translation of an ancient African expression – maalu-a-Maweja, mambu ma/ya Mungu, makambo ma Nzambe – the word theology can never be reduced to the intellectual production of speeches regarding God issued from the only Western and Eastern countries. Theology is originally synonym of African Classical theology, which means Pharaoh’s Egypt, Meroitic, Lunda, Kongo, Zulu, Luba, Dogon, Bambara, Kuba, etc. Considering a Bantu language like Ciluba (D.R. Congo) for example, one should talk of theology in terms of maalu a Mvidi Mukulu (Ntr et logos, maalu a Maweja, maalu a Mufuki). This amounts to talking about «the affairs, issues, things relating to the Creator and the human thoughts regarding Him ».

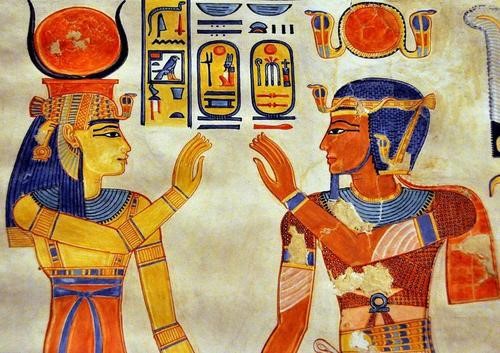

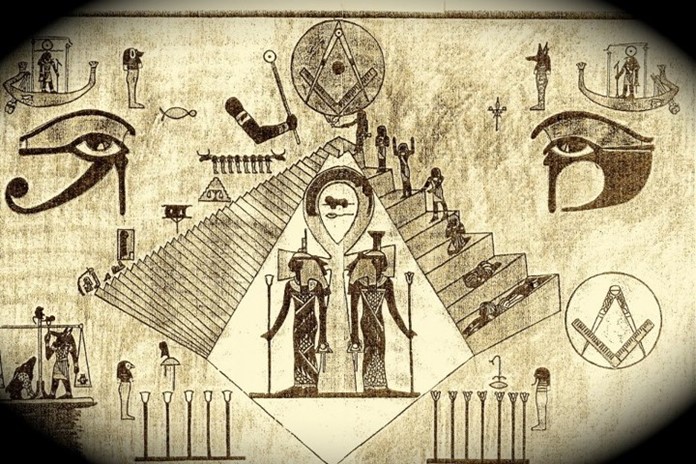

From this point of view, theology has an origin which is distinct from its beginnings. Regardless every ideology, the origin of theology remains in the Nubian and Egyptian civilization in which well known schools of thoughts of Memphis, Heliopolis, and Thebes developed in the past. Later on Greek pupils, who received their training from Black Egyptian priests took up this knowledge and material from their masters which they deconstructed, reorganized in their own way, producing thus a renewed thought under the guidance of Athens. Such process doesn’t belong to the register of the origin; it rather belongs to new beginnings of a received thought which latest actors renovated in the aftermath of Athens cultural influence. On this basis, the colonized nations inherited the Greek-Roman interpretation of the Gospel and started later on their own theology. There would have been, thus, a Greek-Roman beginning which took its origin in Egypt and more specifically Nubia (the nowadays Ethiopia). According to contemporary scholarship, Nubia would be at the origin of human reflection on God. Nubians themselves are convinced that their land is the oldest one to be inhabited by human beings. In this way it can be said that Nubia is the place where theology started.

In the course of time, theological speech took a diversity of colors, depending on the plurality of contexts. That is why it can be spoken today of Christian, Coranic, and other theologies as they are deployed in Rome, Paris, Bruxelles, Ankara, Moscow, Athens, etc.

Since the very past times up to our days, men and women are systematically and in a particular way involved in theological research. They have been granted with the title of “theologians”. In this respect we ask ourselves the question of when one becomes a theologian. In view of experience and for the safe of clarity, it matters to draw attention on some rigorous criteria.

1. One needs first to have been trained by renown masters of certain with an identifiable current of thought. The disciple needs secondly to become himself a master by teaching others. “I brought to you what I myself have received…”. Such are two out of seven criteria, established by Biyogo as he defines the status of philosopher and Egyptologist. Admittedly, this must be recognized, all teachers are not necessarily masters of thought and have not been initiators of specific theological schools (2).

2. Having tried to make one’s own way by developing one’s own thought through theological publications in the strict sense of the term. This requires one’s capacity of thought that distances itself from canonical references of the establishment. From this perspective, we have come to call into question practices which limit themselves to explanations or interpretations of a constituted theology whose superiority toward others cannot be assumed except for dogmatically.

In our work Théologie africaine. Question de method in which we address the problem of method in African theology, we challenge African scholars and intellectuals interested in theology to investigate the new theological locus for African research in theology. This locus is nothing else than Pharos’s Egypt and Nubia. It provides opportunity for a new understanding of the Bible and Christianity itself inasmuch as none can manage a theological investigation without taking into account the prior context or the mother-culture where the collection of biblical texts derived from. In this way, from a strictly hermeneutical point of view, the necessity of such an investigation cannot be denied.

In another of our writings, Une approche afro-kame de la théologie, (which can be translated into English as An African-kamit approach to theology) we underlined the necessity to observe the endeavor of renewing perspectives from the consciousness of challenges raised by the Pharaoh’s Egypt thought which goes back to more than 2000 years before the common era.

In light of this scholarship, it clearly appears that the concept of monotheism is not appropriate for Africa as far as it refers to a kind of opposition to polytheism. On the other hand the term, mono-origin’s reveals able to escape the idea of a Creator opposed to godheads which would have originated from someone else.

Needless to say, it is not our goal to reject the Christian tradition that emerged from Egypt and Ethiopia before it widespread later in a context of domination through other African countries. On the contrary, we aim at revisiting this tradition in guise of a necessary pilgrimage that leads to restitute to several biblical figures their real identity and to get rid of speech in the Bible which diabolizes Africa.

From the African perspective, it is another way of doing theology which removes from the theology of the establishment erected by church institutions.

3. In addition, let us assume that a theologian is the one who takes time to built concept in the frame work of a teaching. For, every theologian is recognized by means of a concept. Being theologian cannot be conceived outside the requirements of a work of theorization made up with concepts and method. In connection to this, let us observe that a range of doctoral dissertations made in Europe does not reflect real investment in methodological research. Works of this kind have been numbered which did not have either thesis or hypothesis. They are mostly featured by a blatant lack of methodological rigor. As a result, a lot of diplomas are deprived of concepts and do not care of all the requirements of theological work.

4. From what precedes, it can be said that not everybody is a theologian. A coherent commentary on a theological, biblical, or Coranic text is not enough to make up one as a theologian. In the context of Catholic Church, it is worth mentioning that a given bishop is not automatically a theologian even if he has got a diploma in theology. For, being tied to the church institution by virtue of the stewardship bestowed on him altogether with his colleagues in episcopate, he can hardly fulfill the requirements of theological truth and draw all possible consequences of theological process. Moreover, the formal training provided for Priestly ordination does not provide the candidate with necessary material for leading a rigorous theological reflection. Every confusion needs to be avoided about an activity which requires revisiting sources, meditation, and renouncement.

5. Before closing this remark, it seems relevant to raise one more question. Can an African scholar who specialized in H. Küng’s work become by that very fact an European theologian? We do not think so. This reminds the formerly distinction made between an “African Review of theology” and a “Bulletin of African Theology”. None would be ashamed to rank the theology of Professor A. Vanneste or Tempel’s Bantoesfilosofie into the heritage of Belgian scholarship. Despite the fact that these scholars discuss African subjects, their works represent theology and philosophy made in Africa. They are not African works as such. However, a scholarly production can be depicted as African when their authors, being Africans themselves, strive to articulate specific problems relating to Africa.

K.S.