At all times and among all peoples, there are men with a rare destiny. Whether he is Bouda, Ghandi, Luther King or Jesus Christ, his role is to be for his people, the helmsman, in the dark times of their existence. It is to this kind of role that Mabika Kalanda indulges, at the time of the accession of Congo Kinshasa to its independence.

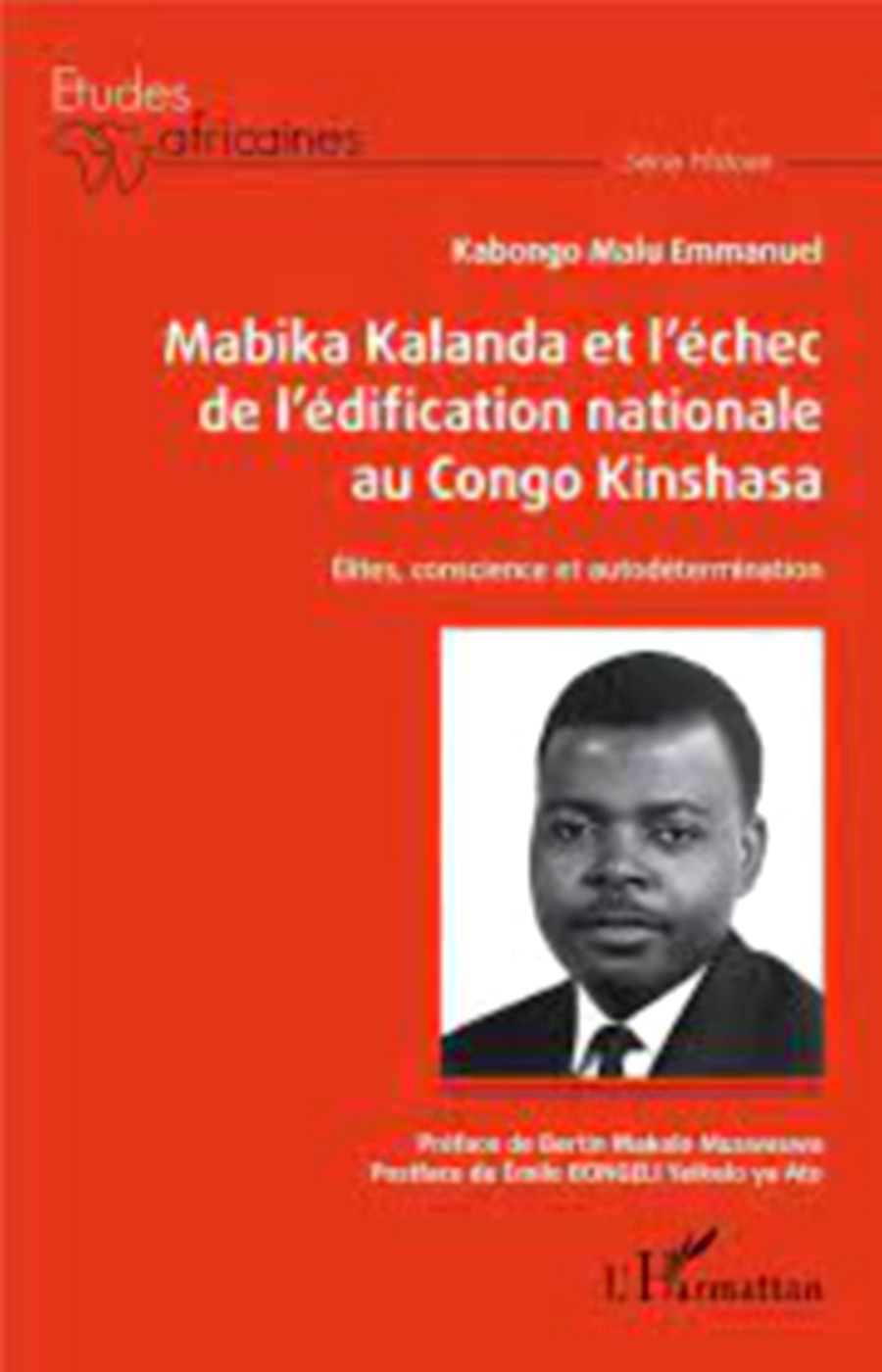

Kabongo Malu dissects in its nooks and crannies the thoughts of this worthy son of the country, who, in his time, sought, through the magic of the pen, to save the Congo from destabilization. A destabilization that has become a constant in the history of the Congo, an evil of the century that still rages today. But who is Mabika Kalanda? A rare swimmer in the stormy waters of the dawn of independence. As Bertin Makalo Muswaswa attests, from the preface, he is “a statesman and a thinker who is linked to the third current which marks the history of the Congolese intelligentsia, that is to say the current that globally rejects all forms of precolonial, colonial and postcolonial alienation. This is undoubtedly the current that Paulin Manwele, SJ, calls “critical sociocultural current”, and about which he affirms that it is recent in African philosophy” (p.5.).

A major question haunts A. in the “diachronic hermeneutics” that he makes of Kalandian thought: “Why has the West succeeded in lastingly exploiting Africa?” Applied to the Congo, this question calls for many others which generally show the responsibility of the Congolese elites in the “debacle” that the Congo is experiencing. These elites, to a large extent, are blamed for the deficits of historical consciousness as an identity widely experienced by the Congolese people and of national consciousness as the basis of national political consciousness.

Without the elites and historical consciousness, the people sink and become incapable of self-determination, of initiating a cultural revolution, one that regenerates man through what is fundamental to him in the light of Mabika Kalanda, the "mental", a glimmer that will make it clear that change, emancipation or “national building” is first and foremost a matter of the Congolese himself and not of others. It is through 7 chapters, in an instructive reading volume, on 420 pages that this truth is demonstrated in depth and breadth.

A principle dear to hermeneutics states that to better understand a text, a speech, a work or a situation, one must “transpose” oneself into what is to be understood. That's what A does A. through the first chapter (p.p. 30-87.). How can we understand the “Congolese debacle” linked to the chronic enslavement of Africa, without understanding the context which prevailed at independence and still prevails today in the Congo. “Thinker of history and the Congolese political crisis, Mabika Kalanda set out, from independence, to note, denote and connote the significant events which impact the life of the young independent nation and ultimately questioned the ground swell that gave birth to them” (p. 30.). From this critical observation, some major lessons emerge, the first and fundamental of which is that we cannot free ourselves from enslavement and emancipate ourselves without the Engine of national history which is the numerous, devoted, loving national elites. their country (p. 31.).

Men of all trades, the elites are mixed up in all sauces. Their historical responsibility is to build the Nation and the State, to detribalize the populations, to politicize the people to make them a national force of resistance to internal and external enslavement, in short to teach this same people freedom as the aim of history (p. 31.). And it is this freedom, once well defended, which is the second great lesson. In the footsteps of freedom, there sprouts a sincere democratic governance, “which is identified in particular with effectiveness, the delivery of public services, transparency, participation, the primacy of the general interest, in short the democratization of Company ". (p. 31.).

The third major lesson is that the exploitation of Africa in general, and of the Congo in particular, by the West is a “struggle for existence” (p. 34.), a “struggle for survival” (p. 35.) skilfully maintained by the slave trade, colonization and globalization. What has not been done, since Leopold II, by little Belgium to perpetuate this fight? What monstrous machinations! Establishment of a false moral authority; installation of a local colonial administration masterfully led by the Colonists; cultural, psychological, political and economic enslavement for the purpose of securing the bases of exploitation; even spiritual enslavement, going, thanks to the support of “savage sciences”, “colonial sciences” and Christianity, to the point of erasing our values, of eliminating the indigenous intelligentsia which is the repository of indigenous historical knowledge; imposition of political caricatures on our Heads of state obliged to stick to the Colonial Charter and International Trusteeship, by which both our neighbors and the cosmocrats find their account in the plunder of our wealth (p. 36- 63.).

So! If this is the drama (economic exploitation, political repression and cultural oppression) of a people dominated and attacked after independence and currently by the imposition of “a slave-like, predatory and failing State” (p. 57. ), one must go on the counter-offensive. And there, the A. appeals to what is in his work an anaphoric formula at the beginning of each chapter: the national elites and their ideological mission to be the architects of change (p.p. 63-72.). The A. speaks of the Elites, and not of the “Evolved”, “….this nationalist petty bourgeoisie inserted, since independence, into the international bourgeoisie of which it serves as a local relay for the overexploitation of the Congo! » (p. 64.). They are also not to be confused with our valiant heroes and martyrs of the Congolese cause such as Simon Kimbangu and Patrice Emery Lumumba.

After the end of this first chapter marked by the postulates of “National Renewal” (p.p. 76-87.) which generally call for a popular struggle for democracy and national sovereignty, comes the second chapter (p.p. 89-116.), which, by highlighting the cultural paradigm at Mabika Kalanda, shows “how the Congolese people and their elites are responsible for their stagnation and enslavement” (p. 89.). Taking advantage of the learned research of Hannah Arendt and Kwamé Nkrumah, this chapter adds that the Congolese elites are even responsible for ideologically nurturing the people and formatting them with powerful political opinions (p. 100.). But such a mission reserved entirely for these elites can only succeed if this people is modeled and remodeled in the molds of the cultural paradigm; a paradigm that highlights the importance of consciousness and history in a man's life.

History is what establishes man as the master and actor of his destiny (p. 110.), while conscience is what allows man to reconcile himself with his reality to bring peace (p. 112. ). It goes without saying that the two, consciousness and history, put together, give us historical consciousness, itself a condition for the emergence of national consciousness, the basis of the “cultural renaissance of the Congolese so that a new, confident man is reborn, patriot, owner of the soil and subsoil, master of his destiny and the institutions that preside over it” (p. 115.).

With the third chapter (p.p. 117-150.), the song of the nightingale as an exit from the tunnel is far from being performed. Can we speak of emancipation where the levers for the emancipation of peoples, namely elites, conscience and self-determination, are not yet united? In this regard, Habib Bourgiba's sentence is significant, highlighted: “Here is a people who have proven themselves incapable of conducting their own affairs and whose leaders are incapable of assuming their responsibilities! » (p. 117.).

In the dynamics of Bourgiba's thought, it is urgent to interpret anew, the eternal and long-standing Kalandian problems which are those relating to "national elites as the exclusive motor of national history because representatives of a culture, the problem of historical and national consciousness as the energizing, securing and developing energies of the Nation and the State as well as the problem of national culture as the societal backbone, without which no society can stand or resist enslaving assaults from outside, nor assert itself as a human entity with a future” (p.117.) It is urgent to “combat the confusion, wait-and-see attitude and fatalism” characteristic of our people (p. 118.) ; it is urgent to ban what the historian Ndayell e-ziem calls “the policy of three monkeys” according to which “the monkey has big eyes, a big mouth and big ears, but the monkey says nothing, does not see nothing and hear nothing! » (p. 121.); it is urgent to understand that our misfortune comes from the covetousness of our wealth and our strategic position in the heart of Africa (pp. 112-123.); finally, it is urgent to look for other rescue strategies because those put into force until now, namely the various political dialogues of which the obvious cases were the Sovereign National Conference and the New Year's Eve Agreements, have given rise to a mouse.

All in all, the Congo of the future that we want to be free, united and prosperous, requires self-awareness through the recovery of historical memory; recognition of our national history; promotion of universities open to the big questions of the moment; linguistic unity and strengthening of the collective personality (p.p. 142-150.).

The fourth chapter (p.p. 151-226.) is the cry of despair. Hence Mabika Kalanda exclaims: “The question of true intellectual elites for our country poses enormous problems! (p. 151). Whether they are from yesterday or today, whether they are few or numerous, they are wrecks good for making the beauty of the ravines, alienated, uprooted, stuck in the mud of tribalism, beneficiaries of a bookish training which distances them from the interests of their Nation for the benefit of colonial interests (p.p. 156-160.). They do not, moreover, play the role of “societal centrality” which makes them this minority which positively transforms society for the benefit of the general interest (p. 161.). Even if we recognize that they are the fruit of a deliberate policy of inferiorization maintained by the Colonizer, they are responsible for many excesses including the politics of the stomach, the mismanagement watered by corruption and the extroversion of the national economy, the corruption of justice, the dictatorship at the top of the State under Mobutu and Kabila Junior, and the confiscation of university education for the benefit of politics, etc.

It is clear that such abuses were favored by the former colonial power which made our elites the servants of an oppressive order. Faced with these excesses, it is urgent for the A., from the Kalandian perspective, to train our elites, with particular attention to young people. It is important to show young people that today's world, through international exchanges, is not a world of clan solidarity, but of calculation and interest (pp. 208-209.).

The new elites must “make ruptures for a cultural readjustment, or even a modernization of their mentalities” (p. 209.). They must urge young people to generally question ancestral heritage and the alienations resulting from colonization; also “awaken in young people a sense of history and the societal consensus that results from it” (p.210.). And since these elites “must take the destiny of society and their compatriots into their own hands, and that, as a result, they must be equipped with well-made heads to avoid chaos in society” (p.211. ), it is also their responsibility to convey the truth as the purifying juice of the economy, politics and culture; a truth which humanizes the people by arming them with patriotic love, courage, sacrifice, ideals of freedom and justice which have made heroes and martyrs of independence into great men (p. 215. ).

The new elites are truly a treasure for the Nation. They fight the policy of servant and perpetual outstretched hand (p.215.). Non-pleasant, materialist and epicurean, they form the people according to the Nietzschean law of 3 metamorphoses: camel spirit, that of man, which swallows everything without criticism; lion spirit, that of the man who revolts; child spirit that of a man, who freed from the prejudices of the world and about the world, becomes creator of a new world where life is good (p.p. 216-220.).

It is all this baggage that ensures the greatness of man in the Kalandian perspective. The three chapters which follow, namely the fifth (p.p. 227-275.), the sixth (p.p. 277-337.) and the seventh (p.p. 339-411.) beat around the bush and do not add much to the defense and illustration of the theses of A. from the Kalandian perspective. More precisely, we must remember this:

- Speaking of the deficit of historical awareness in Congo Kinshasa, the fifth chapter shows the failure of the various national dialogues having only been missed opportunities for national building;

- Still because of the same deficit having consequently led to the deficit of national consciousness, A. deplores in the sixth chapter the heteronomy of political consciousness and material extroversion by the economy and the disruption of the emergence of a national culture since Leopold II and the Second World War, having aggravated imperialism by the Cold War in the country;

- The seventh chapter finally deplores the non-emergence of a middle class in Congo Kinshasa because of a colonial and post-colonial economy leading to the predation and impoverishment of the Congolese masses.

Let us conclude this report. In a limpid and captivating style, free from common errors linked to syntax and stylistics, A. confronts the Congolese with his responsibilities and puts on his lips these words from a well-known song by John Littleton: “Go further. Go further. Even if you think you've arrived. Go further. Go further. The journey has barely begun. And the road is still long.” Plato before dying said: “All that I have said is not all that there is to say.” Kabongo Malu did not say everything, but he said the essential, he reminded the Congolese elite of its role of being the "engine of history", the secret of success in the frantic struggle for advent of a new Congo free from all obstacles on the political, economic and cultural levels.

Moreover, in the farandole of progress, let us stand hand in hand so that this oasis of peace, hope and recreation may come about, called for with all his wishes for Kabongo Malu, the philosopher and the prophet for our time in the epitome he made of Mabika Kalanda's work.

Mabika Kalanda et l'échec de l'édification nationale au Congo Kinshasa: Elites, conscience et autodétermination, L’ HARMATTAN, PARIS, 2020, 420 P.

(Mabika Kalanda and the failure of nation-building in Congo Kinshasa: Elites, consciousness and self-determination, L' HARMATTAN, PARIS, 2020, 420 P.)

By Ernest BULA Kalekangudu,

Graduate of Higher Studies in Philosophy

*This article has been translated from French into English by Marcus Boni Teiga