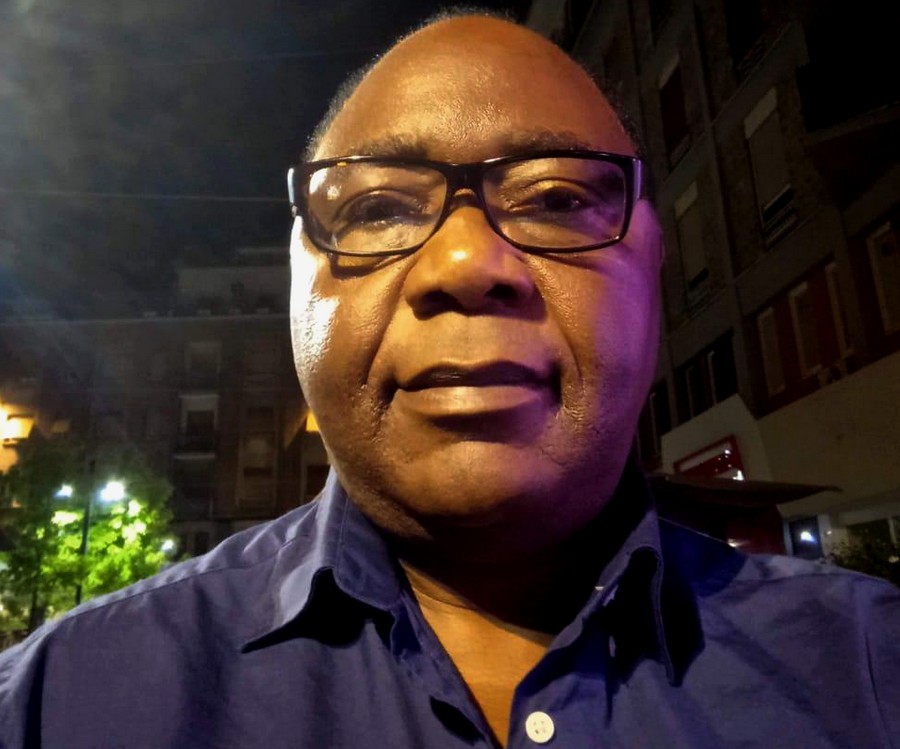

Bossuet, a French man of the Church, preacher and writer, recognized for his unparalleled oratorical verve, said: “Whoever wants to judge well about the future must consult past times.” It is with this thought that Bakadisula Katumba, man of the Church, University professor, researcher and certified observer of political life in the DR Congo for two decades, turns his gaze towards the past and critically examines the hot question of relations between the Church and the State, in the light of Catholic tradition and the justification of the quiddity of the action of the Church in the political sphere under any skies.

Indeed, today more than yesterday, that is to say since the origins of Christianity, the relationship between Church and political power is a fiercely debated and contested question, a centuries-old question which divides and causes much controversy ink. The whole range of possible schemes, from theocracy to the most watertight separation between religion and politics, which reduces faith to a purely private field, has been mentioned, if not translated into practice. Historical development was marked by moments as diverse as mutual suspicion at the time of the first Christians, through the Christianization of the Empire, the quarrels of the Middle Ages for supremacy between political and religious power, the various stages of the secularization leading to the disappearance of the temporal power of the Church at the end of the 19th century, a disappearance which the Holy See took several years to accept. In reality, this acceptance only fully came to fruition with the “Declaration on Religious Freedom” of Vatican II, DC, Nr. 1463, 1966, Col.97-110, which stipulates that “religious freedom… is without prejudice to traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of man and associations towards the true religion and the one Church of Christ.

It is not Bakadisula's purpose to retrace in detail the stages of this process which would require several lifetimes for several men, but to take a position in an important debate. “All the arts which contribute to the well-being of man,” asserted Cicero, “are inextricably linked.” Bakadisula is not from the family of needlessly fiery polemical authors, those who take advantage of their gift of speech to destroy with terrible chatter. On the other hand, he is the builder of a constructive dialogue, with a view to a lasting centuries-old truth. For him, Church and politics are two streams of water that call to each other at the same time as they push each other away. Both, in Congo as elsewhere, are at the service of human being. “The Church only frees itself from the interests of this world to be better able to penetrate society…. », Declared Paul VI to the diplomatic corps accredited to the Holy See in 1966. This, in a few words, summarizes all the great philosophy of the conciliar document “Gaudium and Spes” and subsequent developments within the Church.

Affirming that faith in DR Congo has a social and political dimension is the fundamental thesis that A. of this 213-page work is presented in three chapters of unequal length. Removing from us the specter of unnecessarily long exegetical and theological discussions, the first chapter (p.p. 11-21) briefly determines the juridico-political grid of the foundation of political authority by drawing on two traditions that are both “complementary and contradictory” completed. by “the philosophy of rights, introduced into Catholic discourse by John XXIII, as well as the conciliar recognition of the autonomy of politics” (p.11). These traditions are:

- The theory of political authority of Pauline and Augustinian inspiration;

- The Thomist theory of Aristotelian origin on the common good.

According to the first tradition, everything is underpinned by the principle that “everyone submits to the authorities in charge” (p. 11), “because there is no authority that does not come from God, and those which exist are constituted by God” as Rm 13.1 (p.11) clearly attests. Subsequently, everything that this principle implies is worth its weight in gold, whether it is submission out of conscience exhorting one to pay taxes (Rom 13:5 and Rom 13:7), or whether it is acts in behavior contrary to this submission (Rm 13.2 and Rm 13.3-4).

All things considered, this Pauline conception of power, largely different from our democratic and secular conceptions according to A. (p. 12), is full of lessons. The first teaching is to ask each citizen to fully assume their dual responsibility as a citizen of Caesar's Kingdom and a citizen of Heaven (p. 13) by rendering to these two kingdoms what is due to them (Mk 12, 17). The second teaching maintains that civil authorities and institutions are not evil, they exercise true divine service (p. 13) “Reflecting divine power, they participate in its work. And it is because they are an “instrument of God to lead to good” (Rm 13:4), “to do justice and punish those who do evil” (Rm 13:4b), that they require of all respect and obedience (Rom 13:5). It is therefore up to each person, and especially to each baptized person, to be a good citizen, seeking, in their own time and situation, the broad outlines and concrete modalities of a fully lived and recognized citizenship” (p.13).

Also inspired by St Paul is the Augustinian theory which presents political authority as "a remedy for concupiscence and a means of coercion to force sinful man to cooperate with his brothers" (p. 14), which, moreover, is recognized by John XXIII in his encyclical Pacem in Terris where he “affirms that the principle of political authority comes under divine law” (p.15). “The Council itself,” adds the A., “declared a few years later that the political community and public authority find their foundation in human nature and thereby come under an order fixed by God” (p. 15).

The second tradition, the Thomistic one of political authority, is easy to understand. According to her, the end of any authority or the State is to guarantee and promote the common good. This idea of the State is taken up by St Thomas Aquinas in the wake of the great philosophy of Aristotle. Like Aristotle, St Thomas “considers the State as the societas perfecta in which the natural development of man takes place” (p.p. 16-17).

This means that any State or authority as coming from God of which it is the “instrument” (Rm13,1b.4a), finds its full meaning by putting itself at the service of society by promoting the common good as desired the Council for whom the political community is one “of the social bonds necessary for the development of man… [which] correspond more immediately to his human nature” (p.17).

Against the background of all these premises (St Paul, St Augustine and St Thomas) which no one can brush aside, it is unmistakable that the Church, at all times, plays politics. It is even the explosive title of the second chapter (p.p. 23-162), a subject of caution and the subject of controversy which has become the refrain of the day in DR Congo for years.

Indeed, the Church in DR Congo is not reduced to the prism of the "Hierarchy" alone, but of Koinonia, of communion, of "all of those who believe in Jesus Christ and who organize themselves to lead their lives according to the lines of force that take shape from their faith. Faced with the problems of society, this Church exists as such by taking its part in the efforts of men and women who are committed to building a society loving justice, peace and fraternity” (p.23). The Church's involvement in politics is thus a right and a duty, because, believes Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Rerum Novarum, "the Church draws from the Gospel doctrines capable of either putting an end to conflicts, or at least to attenuate them…” (p.26). Paul VI says it even better in the encyclical Populorum progressio when speaking of the Church as “Expert in humanity”. “Expert in humanity, the Church, without in any way claiming to interfere in the politics of States, has only one goal: to continue, under the impulse of the consoling

Spirit, the very work of Christ (…). Communicating with the best aspirations of men and suffering to see them unsatisfied, the Church helps them to achieve their full development, and this is why it offers them what it has of its own: a global vision of man and life. 'humanity' (p.27).

The scene thus set gives full meaning to the intervention of the Church in DR Congo through its hierarchy, in very diverse political and social contexts” (p. 27). There is no doubt that, while recognizing the political community's mission to achieve the common good (p. 35), one also recognizes that of the Church enlightened by faith and reason, to guide political choices for the benefit of the dignity of man and the common good, without falling into a foggy and senseless activism which distorts relations between Church and State (p.p. 36-37).

What about this activism under the Second Republic? In his book The Age of Dictators (2019), Jean-Pierre Langellier briefly describes the Mobutu dictatorship in these terms: “For nearly thirty-two years, from 1965 to 1997, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu reigned with an iron fist on the former Belgian Congo, renamed Zaire (today DRC). He imposes a ferocious dictatorship combining blood crimes, corruption and shameless pillaging of national wealth.” Faced with this dictatorship, the Church could not remain silent. It denounced, under the leadership of the energetic Cardinal Malula and the CENCO, through memoranda, letters, declarations, messages and even marches, the excesses of an autocratic power, incapable even of recognizing the achievements of a national reconciliation forum called the “Sovereign National Conference” (p. 36-57), a last chance meeting and a memorable opportunity to develop a new social project for the Third Republic (p. 53).

A concluding word on this prophetic impulse of the Catholic hierarchy during the period under examination is that it encountered more than once threats and intimidation from those in power, going as far as persecution.

The Third Republic! Rich in twists and turns, it offers the Catholic prophetic impulse a favorable humus, especially under Kabila father and Kabila son. Under the father, the bishops attacked a foreign Rwandan presence in the sovereign institutions which ended up, in the long run, imposing a war of aggression on the country (pp. 57-64) and the ignominious assassination of this same father, himself becoming president through the AFDL rebellion in 1997. Under Kabila Jr., the dictatorship returned at a gallop to inhuman proportions. A cascade of assassinations, forests and mining plots ceded to multinationals and the truncated elections of 2006 and 2011 speak volumes. Faced with this horror, the bishops did not delay, helped by the Lay Coordinating Committee (CLC), to govern through declarations and marches.

When on 12/30/2018, Félix Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo was proclaimed President after the elections, the prophetic momentum of the Catholic hierarchy crumbled, he became a partisan because of the divisions that were tearing CENCO apart. As proof, the truth of the ballot boxes is contested without sufficient evidence (p.p. 97-109). Three, four years later, this crumbling worsens through what A. called “political differences within religious denominations regarding the CENI” (p. 124). What a mind-blowing drama! While the government has weighed its means to set up a neutral CENI representative of all tendencies, the CENCO and the ECC, in collusion with Kabila's FCC, are stepping up to challenge the CENI in relation to its members.

In this Byzantine-style debate, the board of directors of this sensitive commission is contested, not based on its skills, but on ethnicity and tribalism. The A. of this book, did he not publish another more suggestive book, “Ethnicity, tribalism and “Congolese disease” in D.R. Congo”? This is the deep evil, the very one that guides the bishops who fight, despite the very relevant observation of the “constitutional scholar, prof. André Mbata, who chairs the legal commission of the Assembly (p. 127) according to which “the CENI is political par excellence” and cannot become the prerogative of pressure groups whose objective is none other than conquest and the exercise of power” (p.p. 127-128).

Finally, in a debate so decisive for a new political era in DR Congo, there is cacophony. Because sometimes, we attack (CENCO and ECC) Ronsard Malonda as president since he belongs to the defunct CENI of Corneille Nanga, sometimes Denis Kadima since he is from the geographical area from which the President of the Republic comes. The debate will continue even for the CENI reform of July 2021. Hence today, the chaos which exists before the recurring crisis of legitimacy for credible elections.

Faced with this debacle, “several citizen or political initiatives had already put forward proposals to restructure, reform and depoliticize the electoral commission” (p. 227), but without convincing results. It seems that we are going on a crazy tour, because at each point of arrival, new debates arise such as those linked to "the electoral register, voting methods, the financing of political parties, electoral disputes and access to media” (p.p. 129-130).

As a keen observer of the political scene, A. notes that there is no need to play Afropessimist to resolve the crisis which pits the State against the CENCO and the ECC against the CENI. It is necessary, he underlines, to resort to the proposals of the Congo Study Group (GEC). Among these proposals, it is recommended to put two devastating waves out of harm’s way:

- Tribalism in religious faiths (pp. 130-146);

- Politicization of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church (pp. 147-162).

The dethroning of these two waves from the top of their pedestal gives the A. to approach the third and final chapter (p.p. 163-183). Jacques Maritain, French Christian philosopher, in one of his beautiful thoughts, proclaims: “The end of political society, like that of all human society, implies a certain work to be done in common”. What would we gain, Church or State, in this D.R. Congo coveted on all sides, from rowing against the current, to evolving on an island cut off from any port?

And yet, Robinson Crusoe, even on his desert island, felt invaded by others, if only by the wreckage of his ship. This is what the State and the Church are invited to do in the third chapter. This is “partnership”, “healthy collaboration”. “The normal and fair way for the Church to do politics is not to descend into the terrain of the power struggle or to become the spokesperson for political parties. Its mission is to illuminate human problems with the light of the Gospel, to form new men capable of guiding politics and making practical choices according to the values of a humanism open to God.

There is no doubt that this collaboration quickly turns into harmony, as recognized by Mgr Utembi cited by A. : “We are called to collaborate, to work together, the temporal, the political, the religious, all must combine efforts to serve the people who must be the center of our concern” (p. 174).

Moreover, the commitment of the Catholic Church in the fight for a more just and democratic Congo will bear a hundredfold fruit if and only if it relies on the laity, its secular arm (p. 176) for action. “There is therefore an urgent need for Christian formation. In the current context of a society that is both global and diversified, local and planetary, the lay Christian needs, to act, professional training (continuous, permanent), Christian or religious training (theological training, spiritual), and a human formation” (p. 178).

At the end of this report on a book with a crystal-clear style, A. deserves our vibrant tributes. Senghor said: “The happiness of being together should not eliminate our differences.” Church and State in DR Congo will always face the same fate. “Why hate us? We are united, carried away by the same planet, crew of the same ship,” said Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Bakadisula is a visionary. He makes us understand that nations never rise up in division and hatred, “since,” says Boudda, “hatred will never cease with hatred, hatred will cease with love.” A verse from Terence, comic poet Latin, says: “I am a man and nothing that is human is foreign to me.” The globalized context in which we live, with its millions of human tragedies, invites the Church and the State in DR Congo to come to terms, to agree for the development of the Nation. Because, concludes the A., “in fact, the Church is a social actor, that is to say producer and founder of forms of existence and gathering. By structuring itself institutionally, it ensures solidarity and a certain sustainability of the common ideals which bring together men” (p. 186).

At the end of this report on a book with a crystal-clear style, A. deserves our vibrant tributes. Senghor said: “The happiness of being together should not eliminate our differences.” Church and State in DR Congo will always face the same fate. “Why hate us? We are united, carried away by the same planet, crew of the same ship,” said Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Bakadisula is a visionary. He makes us understand that nations never rise up in division and hatred, “since,” says Boudda, “hatred will never cease with hatred, hatred will cease with love.” A verse from Terence, comic poet Latin, says: “I am a man and nothing that is human is foreign to me.” The globalized context in which we live, with its millions of human tragedies, invites the Church and the State in DR Congo to come to terms, to agree for the development of the Nation. Because, concludes the A., “in fact, the Church is a social actor, that is to say producer and founder of forms of existence and gathering. By structuring itself institutionally, it ensures solidarity and a certain sustainability of the common ideals which bring together men” (p. 186).

Author: Crispin Bakadisula Katumba Madila,

Title: The Catholic Church of the DR Congo in politics (L’Eglise catholique de la R.D. Congo en politique)

Publisher: Editions Croix du Salut, Chisinau (Moldova)

Publication date: 2022

Number of Pages: 213 pages.

By Ernest BULA Kalekangudu,

Graduate of Higher Studies in Philosophy

*This article has been translated from French into English by Marcus Boni Teiga