The Egyptian crisis, following the Arab revolutions, led to the fall of ex-dictator Hosni Mubarak and the advent of the Muslim Brotherhood, headed by President Mohamed Morsi. But hardly had they settled in power than the real actors of the revolution began to become disenchanted with the Islamist excesses of the regime.

On December 5, 2012, in Cairo, the now famous Tahrir Square is again occupied by thousands of demonstrators hostile to the new President Mohamed Morsi, from the Muslim Brotherhood, but democratically elected. It is that since the fall in February 2011 of the ex-Raïs, Hosni Mubarak, the authors of the revolution believe that the Islamist movement of the Muslim Brotherhood robbed them of their victory. And not content with that, he wants to impose on them a Constitution of theocratic inspiration. In a country that has more than 10% of Coptic Christians and many Muslim supporters of secularism, the pill is struggling to pass. And the anger of the street rumbles.

And for good reason, in the streets of Cairo, the second revolution is in full swing. Every day, more and more demonstrators occupy Tahrir Square to demand answers to the country's economic problems, a secular constitution, even the departure of President Mohamed Morsi. Between these sociopolitical demands and the harsh economic realities that the Muslim Brotherhood regime had to face, Mohamed Morsi and his people are clearly between a rock and a hard place. Faced with this situation, Egypt has no choice but to appeal to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Which issued its requirements before untying the purse. In other words, a kind of drastic structural adjustment program. Because the situation of socio-political instability is not to reassure the IMF. Even less the economic and business circles. Indeed, the tourism sector on which the country largely depends is still struggling. Tourists are becoming increasingly rare.

Shortly after the fall of ex-dictator Hosni Mubarak, some Egyptians are already beginning to miss the good old days of old Raïs. Called to order in this by the harsh economic crisis which is hitting the country with full force. Food prices are soaring. The fuel is running out, and you have to stand in long queues to get a few drops. The major tourist sites remained eternally almost deserted, with the exception of a few rare people who still venture there.

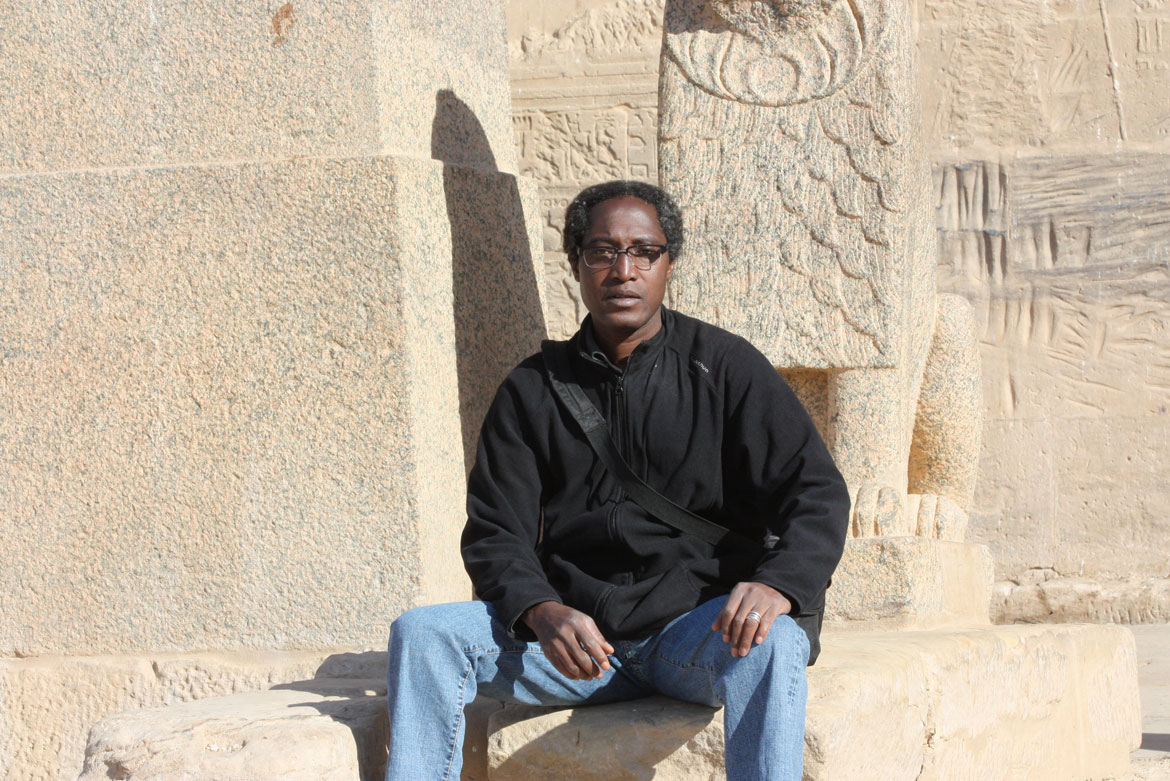

Usually, the Luxor souk is busier than it is today, shopkeepers tell me. Those who harpoon me to try to sell me their objects, try to convince me that they are giving me the best price because there are not many tourists. I am attacked from everywhere. I can see for myself that there are not many tourists walking the aisles of the souk at this hour. However, I don't want to be trapped. I continue my hike and hear someone calling me “Nubian” from a shop. He is one of the few Nubians to have a shop in the market.

I stop in his shop. We are talking. He offers me tea, and we talk about the Nubians and Aswan, my next visit. I buy him a silver chain on the cartridge of which I register the diminutive of my authentic first name "PIYE". Then, he makes a point of warning me not to be scammed on any objects that I would buy. We part with the promise that he will come see me at my hotel: Susanna Hotel.

On this December 7, the inhabitants only talk about politics. A pro-Morsi protest is scheduled to take place in the streets of the city. And against all odds, it is at nightfall that it takes place. A sparse march of support, bringing together no more than a hundred individuals, rather young, making more noise with their concert of horns as if to compensate for their numerical insufficiency. The next day, December 8, the opposing anti-Morsi camp also responded by occupying the streets of Luxor with a few more demonstrators than their opponents the day before. On December 9, in this already very tense context, ousted former President Mohamed Morsi had no choice but to cancel and postpone the referendum on the Constitution initially scheduled for December 15, which he proposed to submit to the Egyptians. This retreat under the strong pressure of the demonstrators in Cairo who had almost attacked the presidential palace by attacking the barbed wire erected against them, was only Act I of the second Egyptian revolution.

Due to the lack of tourists in this high place steeped in history which, thanks to the temples of the city and that of Karnak, not to mention the world famous Valley of the Kings, attracted a plethora of visitors, I take the opportunity to visit many sites quietly: My Mummification Museum, Luxor Temple, Luxor Museum, Karnak Open Air Museum, Temple of Hatshepsut, Ramesseum, Coptic Monastery, Temple of Ramses II, Colossi of Memnon, etc.

I cannot visit Egypt without going to Aswan. Meeting Nubians in their midst is a moment that I have been waiting for for a long time. From Luxor, we leave on December 15 with a taxi, in the early morning. All along the route to Edfu, we discover the importance of the Nile in the life of the Egyptians. On both sides of the great river, fields spread out. And from these fields come heaps of banana bunches, tomato baskets, sugar cane stalks and various food products that vehicles converge on different markets or factories.

Anciently, Egyptian Nubia began at Edfu. We cross the city towards Kom ombo. And there, first stop to visit the Temple. A few meters from the river stand columns of the said temple on which one can read all the figurative expression of the artists of ancient Egypt. Below, is the craft village made of straw huts topped with the superb domes that are the living symbol of ancient Nubia.

After a few minutes of stopping, we continue the road towards Aswan. Along the way, villages perched on hillsides and shimmering colors are offered to our eyes, beyond the other bank. Finally, we arrive in Aswan. At first glance, it is obvious that the city is now artificial. Rather touristy, with its endless hotels and two-storey houses. The capital of Nubia is no longer truly Nubian. Since the construction of the Aswan dam, the Nubians have been rehoused, at least parked about ten kilometers from the city. Unlike other Egyptian cities, there are many more black people here. Normal, we are in the heart of Nubia.

In the early afternoon, I go to the Nubia Museum. We owe its realization to UNESCO. The many remains that risked being engulfed by the waters of Lake Nasser during the construction of the Aswan dam in the early 1960s are gathered there. With its 3,000 pieces and from all eras, there is plenty for the visitor to see. Any African who visits this museum, which is one of the largest in Egypt, is struck by the extraordinary decorated pottery bowls dating back 6,000 years and whose similarity to those still found today in Black Africa is surprisingly real.

My first encounter with Nubians from Aswan was with one of the museum curators and his brother. At the end of my visit, we take the time to chat for a few minutes. Then, I go to an appointment in the so-called Nubian village, with Joseph, a colleague who works in television. The welcome is worthy of the return of a child prodigy. Joseph receives us in his living room, introduces us to his wife. She hastens to ask us what we would like to drink, and we accept tea.

In fact, they are parked like Native Americans are parked in the United States. Isolated from the city of Aswan itself. The Egyptian state had made great promises to them during the move. The beautiful houses that were dangled to them are now only HLMs, and the land for these peasants in the majority is still unfindable. The same is true for socio-community infrastructures such as hospitals and schools.

In any case, we avoid dwelling on angry subjects to talk about our common origins. Language is the only bond that still binds us. And the words are not lacking to remind us of it. Joseph tells me that "Mi Nabo" means my king in Nubian. I tell him that “Mi Nabo” also means the same thing in Nateni, my mother tongue, except that this word now comes from the old Nateni. Amazing, isn't it? But in reality no, because all Negro-African languages have a common substrate. Every African, wherever he is, therefore carries within himself a part of eternal Nubia. Our exchanges end very late. We promise to meet again. Maybe one more day.

December 16. Early in the morning, we leave for the pier from where the boats depart for Philae. But in fact, we should say Aguilkia. Because, of the ancient ancient city of Philae, there is only a small piece of rock left. The ruins are certainly moved to Aguilkia but the name of the old city has replaced that of the new site. Philae was indeed the first nome of Upper Egypt, the one which gave its name of Ta Séty or Land of the Arc to the whole of Nubia. What impresses when you go to the island of Philae is the chapel of the Temple of Hathor and its kiosk of Trajan. Both in their design and in their finish. Masterpieces of architecture and engineering. Leaving this island, one cannot help but recognize that UNESCO has done well to save its ruins.

Currently, all of Egypt deserves to be saved. Not by UNESCO but by its own sons. Due to the critical socio-political situation that the country is experiencing. The ancient history of Egypt, however, shows us plenty of examples that it fell several times, but it always knew how to recover. She must therefore recover today. Complete its new democratic transition and regain its rightful place in the international concert of nations. Because Egypt is one of the three pillar countries on which Africa relies to serve as a train for its rebirth, namely Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt. We must therefore know how to keep reason and avoid chaos at all costs, in order to look to the future together. Beyond the sectarian socio-political and denominational considerations that contribute nothing to the progress of the country.

By Marcus Boni Teiga