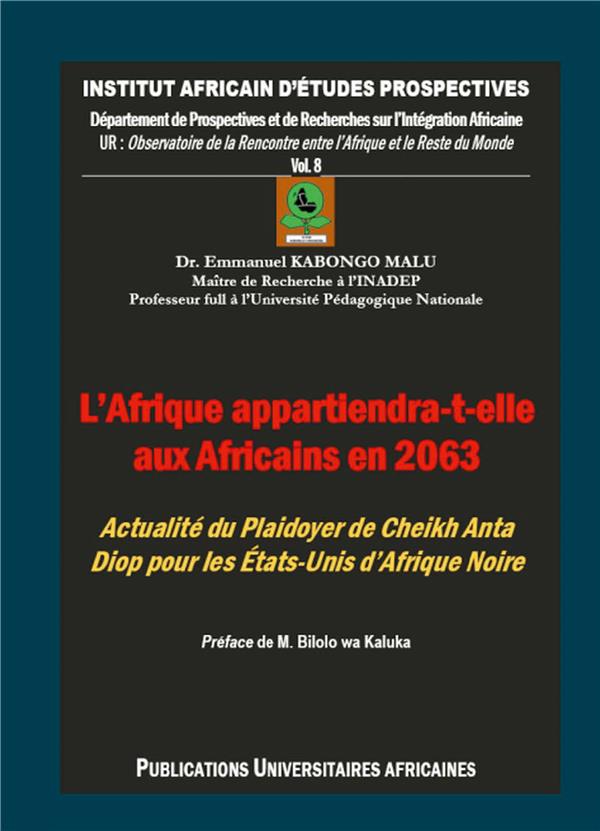

At a time when, in this first quarter of a century, various publications on the new face of Africa are jostling on the horizon, an author like a rare star in the firmament of research, makes his voice heard by not playing the cassandras. This is Mr Emmanuel Kabongo Malu, Master of Research at INADEP (National Institute for Prospective Studies) and University Professor.

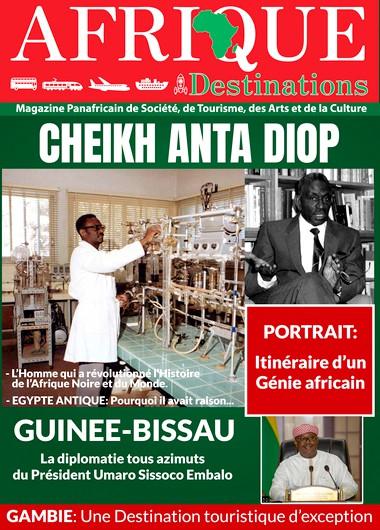

The reflections it offers to lovers of Africa who have no homeland are condensed in an aesthetically beautiful volume like the plumage of the nightingale and spread over 4 chapters across 312 pages. Basically, this jewel of "retrospective and prospective analysis" on Africa, scrutinizes "the news of Cheikh Anta Diop's advocacy for the United States of Black Africa". Who is Cheikh Anta Diop? Endowed with a prodigious intelligence which has made him the classic of scholarship in Africa, this Senegalese is the author of “the theory of a deeply African ancient Egypt. »

Such a plea, which is also part of a vast, beautiful and ambitious project, portends apprehensions not to be taken by the small end of the telescope. Hence, in a subtle and upstream way, the question posed by A. from the title: "Will Africa belong to Africans in 2063?". Apprehension is not a difficult word. In the context of the advocacy dear to Cheikh Anta Diop, he infers that the Altermondialists and the pan-Africanists, without setting back A. himself, feel fear about the future of Africa, starting from a status quo where, in the concert of nations, says Bilolo Mubabinge, "..... the Vultures continue to carve up and devour Afudika and that Ben–Afudika are in permanent danger of extinction” (p. 21).

But what are the different sequences that contribute to a better understanding of the book by appropriating its content? First, there is the preface (pp.11-25) by Bilolo Mubabinge which brings to light in an original way the topicality of the free software project; then, the prolegomena or the introduction which show that the problem which concerns A. is part of the history of a vast field cleared by the cohort of valiant pan-Africanist researchers of which Cheikh Anta Diop is the most instructive representative; finally, before soaking up, in the appendices (pp.297-312), publications of A. and lighting on the key elements of INADEP's Mission, Congolese and European sides, the 4 chapters, as architectural columns that give it solidity and consistency.

Let us develop these sequences by showing how they contribute to bringing the major articulations of the book into the clarity of the logos. After unpublished considerations on the exploitation of the African continent by the Slave Trade, Colonization and Globalization, the preface salutes in the book the Alarm triggered "for our peoples, for researchers and for the leaders of our beautiful and rich Continent, on the threshold of this new year. (pp. 24-25).

The introduction (pp. 27-79), unusually long for a 312-page book, provides the prerequisites for understanding the dream that inhabits Cheikh Anta Diop, this leader of pan-Africanism. This dream is to see the birth of an Africa united and united in a federation as a geostrategic mass like the United States of America. To understand such a project, disproportionately ambitious and having attracted Cheikh Anta Diop, rejection and hatred on the part of the Euro-American geostatic mass, is to understand what the African Renaissance consists of. What to say in summary and shortened presentation?

With the insight of an eagle at high altitude facing its prey, Cheikh Anta Diop guts the boa dreaming big and to the chagrin of the cosmocrats. Its ambition is to revive Africa, which has become a ship adrift, crushed and subjugated by the imperialist West, "by endowing it with a cultural memory for the purpose of restoring African historical consciousness, the backbone of any emancipation of peoples” (p. 27).

Taking the opposite view of the harmful effects of a retrograde war of the imperialist West against the black world since "a slave trade which destroyed moreover all the opportunities for development on the continent and a century and a half of colonization which alienated Man, African version and balkanized the living space of Africans" (pp. 27-28), this cultural renaissance, better still this vast rescue operation, aims to restore the history of the African continent "from prehistory, through a multidisciplinary scientific research by “falling against all odds”, as he himself says, on pharaonic Egypt” (p. 32).

It emerges from this restitution a strong link between History and Politics, implying consequently a junction between the past, the present and the future. The political path and developments opposed to established patterns of thought must revive African culture from the Pharaonic Egyptian heritage and the promotion of Negro-African languages (p. 29). History and language as pillars of the consciousness of peoples and their culture are at the same time founding and justifying the construction of a federal state. “It is up to culture, emphasizes the A., for the salvation and balance of peoples, to inspire politics, to think about it, to animate it” (p. 29).

In the meantime, it goes without saying that the restoration of historical consciousness requires African nations to develop Egyptology in Black Africa and to revisit the Nubio-Egyptian Civilization in all areas. Such a burst being a continental emergency resulting in a federal state guarantees the development of Africa and ensures its viability by creating an army of the pan-African federal state.

But this junction of the cultural and the political whose right of citizenship is recognized among researchers from Western countries has been taxed as an “act of intolerable nationalism” by the Western intelligentsia (p.32) and earned Cheikh Anta Diop “a almost neurotic hostility" (p. 33) and yet it helps to go to war not only against white supremacist ideology, "the very one which is at the root of so many catastrophes for all humanity and especially for 'man, African version' (p. 36), but also against all the new modes of enslavement to annihilate Black Africa and despoil its living space (wars, terrorism, famines, land acquisitions, immigration via the Mediterranean, etc. )

If we have to sum up, the African Renaissance, through the restoration of the memory of history as well as the recapture of the historical consciousness that results from it, aims to restore the autonomy of the African political consciousness carrying the historical initiative. Indeed, in a situation of autonomy, the human conscience moves only according to the vital interests of its existence. This is why, the palpable result of the recapture of the African historical initiative will be seen in the emergence of the great powerful geostrategic mass – the United States of Black Africa to access a dignified life” (p.41). The added value that emerges from such an educational dossier is justified by the following values: the priority of national interests in everything we undertake; a democratic claim based on non-foreign political traditions; promoting science inspired by our culture; the advent of a cultural and intellectual renaissance marked by the establishment of Egyptian-African humanities based on the pharaonic (ancient Egyptian and Coptic); linguistic unification around Swahili; the refusal of the physical fragmentation of Africa into small miniature states, of the psychic balkanization of its people, of the mutilation of historical consciousness having obstructed the autonomy of African political consciousness in favor of heteronomy; rejection of globalization, etc.

All in all, the terminus ad quem of Cheikh Anta Diop's reflections is the emergence of the large Geostrategic Mass described on pages 52-58. The alarm bell is ringing! Now, let's see how the 4 chapters of the book contribute to the in-depth understanding of these reflections.

Under the words and sentences of the first chapter (pp. 81-110) a debate is triggered in which the cosmocrats (those who dominate the world) are reproached for working day and night for the annihilation of Africa, and this, with the brutality of an enfant terrible. Served copiously by the power of the armies and that of finance, these new masters of the world, i.e. the donor States, the Bretton Woods institutions and the Multinationals, maintain their stranglehold on Africa by reducing it to a simple reserve of raw materials. , the cultural rape inducing the loss of the sense of its historical destiny and the non-recognition of its autonomy. These are the obvious facts of a homelessness stigmatized by A. when he says: "the assurances in the existence of the process of obliteration of Africans are observed in that the same actors specialized in the irreversible destructuring of peoples are today at work in Black Africa, using the same methods of enslavement to rob Africans of their living space and send them back to wild and exotic reserves like the USA or to inhospitable corners of the Continent! (pp. 82-83).

In a subtle way and in violation of the sovereignty of States, the spiral of nihilation will worsen with "other weapons of massive destructuring aimed at Africa". Of these weapons, it is advisable to retain in the first place money or debt, which, veiled under the cloak of aid, is killing Africa by asphyxiating it in a chronic dependence which "undermines savings, investments premises, the establishment of a real banking system and the spirit of enterprise” (p. 95). It must be said that like an ogre helped in his work room by "the famous debt service" and "the other malice of the World Bank which is the so-called "Heavily Indebted Poor Countries" (HIPC) initiative, the we have “succeeded in the gamble of the century: the transfer, under the leadership of the WB and the IMF, of African resources and companies to Western multinationals under the fallacious pretext of canceling African debts! (p. 95). Basically, the horror engendered by the debt as well as the old Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) is provoking a monetary servitude for Africa which subjugates some of its currencies to the euro and prevents it from defending its wealth and its own interests (p. 95).

Secondly, as a "weapon of mass destruction aimed at Africa" there is the law, which, on the one hand defines "legal norms through treaties and institutions such as the Criminal Court, ICC (the prison of Africans), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the WB, the IMF, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the Paris Club, OHADA…” (p. 96), and on the other hand, imposes the nebulous “International Community” as a license for any Western country to kill, to set itself up as a giver of lessons and a maker of “kings” for the purpose of destabilizing Africa! (p. 96).

The description of this right in its two aspects is staggering (pp. 96-97) and takes the breath away of any discerning mind and robs Africa of all responsibility in the management of world affairs. Secrétant, underlines the A., quoting ONANA, "a two-speed injustice, established to enslave Africa" (p. 98), this international law has created horrible dictatorships and brought to naught any spirit refractory to its vision by assassinations and elections leading to the favoring of a parasitic and comprador elite.

Backed by money and law as other means of enslavement are violence, the UN, cultural oppressions and symbolic violence. What to say?

- Violence. It is first symbolic through the boulevard of the major Western media which maintains Afro-pessimism. There is no doubt that this violence is related to white racism which defends “the secular Eurocentrism paradigm which determines everything else: the human “races” are unequal and the Black African one is inferior. (pp. 99-100). Then, this symbolic violence or racism is material and is translated in its virulence by wars, attacks and attempts at balkanization here and there and makes victims in incalculable number;

- The UN. The United Nations, says the A., “is the major legal card of the West in the enslavement of Africa” (p. 102);

- Cultural oppressions. It is the arsenal of instruments (ideas, images, books, films, music, etc.) by which "Whites, according to Marcus Garvey, reinforce the idea that their culture is taken for granted, that their culture is in fact simply human nature to be shared by all. (pp. 104);

- Symbolic violence. What is? is this not the anthology of everything that is imposed on us in contradiction with our own culture in order to "weaken us and thus maximize exploitation" (p. 105) Let us cite as examples homosexuality, foreign languages and populations as well as all their cultural objects (pp. 105-108).

The warning to conclude this chapter is the fight against the physical, mental and political degeneration which makes us "a tool in the hands of comocrats", a slave without a say in the concert of nations, a people incapable “to avoid being the future human outlet of the overflow of the world”. Faced with these gloomy prospects, is it not time to ask two questions: why this status quo and what can be done to curb it? Is this the subject of the second chapter?

An intellectual not only being the one who criticizes, but also the one who proposes solutions, A. shows it in this second chapter (pp.111-164) by asking two questions “Retrospective question: why is Africa subjected to such enslavement? Prospective question: what should Africa do in the face of such processes of nihilation? (p.111). In response to the first question, A. brings to light a constellation of forces or facts, which, throughout the history of Africa, crystallize as parameters that lead to the annihilation of an entire Continent. In this order, one can evoke, without much comment, the crumbling of Africa into "a dust of weak and powerless states" incapable of ensuring their own security and of resisting the greed of the cosmocrats, the cretinization of a continent through the amputation of its historical consciousness and its ossification through wars and purposely maintained divisions, the absence of responsible leadership, alienation due to capitalist exploitation, white racism preaching Eurocentric Africanism and globalization seeking to establish global governance for the benefit of the West, etc. (pp.111-137).

All these unseemly facts cannot, observes the A., leave us passive. Martin Luther King said, "What frightens me is not the oppression of the wicked, but the indifference of the good." Against these facts, a struggle must be opposed. This struggle must begin with the education of the masses. An education that provokes awareness for unity. To educate a people is to help them understand what increases their ignorance, it is to sensitize them to become actors in their history, to forge their cultural identity. This cultural identity, which is nothing other than historical consciousness, gives a people who want to be worthy the collective identity.

There is nothing more marvelous for a people than to build a strong collective identity which “is seen as the surest security screw against external aggression” (p.141). It is defined “in terms of lineage, religion, language, history, values, habits and institution” (pp.141).

This collective identity is not something arbitrary. It has material bases. Apart from the concrete facts related to it, it rests, in other words, on our own history already elaborated and recognized by the Africans themselves. In addition, through the brotherhood it promotes among Africans, it makes possible the autonomy of African political consciousness and allows them to reconcile. “Through reconciliation with themselves, underlines the A., Africans will rediscover the psychic, political and social unity which they now lack for the emergence of the United States of Black Africa. Through reconciliation with their past, Africans will recover their cultural, scientific and political greatness, that is to say the historical, political and scientific initiative (p.145).

Without this perception of the unity of Africa on the cultural, scientific, political and even geographical levels, the advent of the United States of Black Africa, like El Dorado of tomorrow's Africa, resourcing itself at the pots of l pharaonic Egypt becomes a bluff. Let us remember, without slavishly repeating ourselves, that Africa grouped together as a federal bloc will have the following crutches:

- The obligation of the Egyptian-African Classical Humanities as a gateway to our collective historical memory through direct knowledge (p. 149);

- The restoration of African historical consciousness through history which allows us to rediscover our humble origins and to redo the path traveled by our ancestors (pp. 151-153);

- The restoration and strengthening of African historical consciousness through the channel of the socio-educational apparatus (pp. 153-156);

- Pharaonic writing as a place for strengthening African historical consciousness (pp. 156-157);

- The imposition of Swahili as a place for strengthening the pan-African national and federal identity (p. 159).

With the third chapter (pp.164-204), A. wonders when Africa bruised by a "tragic diachrony" will become united, strong, free and prosperous on a world stage where different geostrategic blocks compete in hatred and power. To answer this question is to say what it is about the "African Renaissance", this great current of thought and action, initiated by the cohort of valiant Pan-Africanists of which Cheikh Anta Diop is the most powerful representative, and that the A. salutes "as a historic moment", carrying "ultimately the urgency of highlighting an African Discourse by Africans for Africa from their history as intelligibility, as the supreme stage of liberation of the continent black of all subjugation” (p. 181).

It must be recognized that the key ideas of this chapter oscillate between two poles: negative and positive. The negative pole represents everything which, through the slave trade, colonization and globalization today, has erected and still erects itself into a powerful brake on the development of Africa and the construction of a Multinational African Federal State. The positive pole is that of the current of the African Renaissance. It is the current of Memorial Reconstruction, the great ideology of the 20th century according to its protagonists, which, while advising us to have a critical look by "trying also to show what is today the weight of endogenous factors and internal factors in the perpetuation of underdevelopment" (p. 196), reminds us that the great challenge to be taken up for Africa is the challenge of development through a no to imperialism in all its forms and a yes to the Unity of Black Africa, “pledge of true independence whose assumption is in the advent of the federal state of Black Africa” (p. 198).

Finally, what to remember from the fourth and last chapter (pp.205-290)? There exist in the world of our time domains “which establish the power of nations and the joy of peoples”. For A., there are, in the wake of Cheikh Anta Diop, four, namely economy, industry, science and politics. Very unfortunately, these areas that this chapter studies in depth, reflect fragile faces, which mean that in 60 years of independence, Africa is still far from continental political, economic, industrial and scientific federalization.

Indeed, the cross-cutting concept that best sums up this fragility is that of “marginalization”. Africa is marginalized in the concert of nations as a late comer. Economically, it is a poor continent despite its material assets (natural and energy resources) and immaterial (History), landlocked and closed to any competitiveness, an economy of extroversion and dependence for the benefit of the interests of Western powers, an economy which does not resist international competition and which struggles to draw inspiration from solid pre-colonial African economies and which struggles to integrate into the neo-liberal economy. From an industrial point of view, Africa lags behind both qualitatively and quantitatively despite the presence within it of the prerequisites for industrial development. The lack of a precise and structured plan for industrialization means that we are sailing by sight. On the scientific level, especially that of technoscience, in the aspects of scientific research and technological production, the absence of Africa is remarkable. Politically, Africa is far from belonging to itself because it is governed by a parasitic elite and without responsibility in the bodies that run the world (UN Security Council) and certain forums of global interest.

If we recognize at this stage of reflections that Black Africa is "off to a bad start", it needs a vast rescue operation which is nothing other than the African Renaissance. More than just a battle cry, the African Renaissance is a new way of life. Its key principle is the unity of Black Africa, “a pledge of true independence whose space of assumption is the federal state of black Africa” (p. 275). This Unity, dependent on the appropriation of our historicity and the historical consciousness that unfolds from it, must be driven by the African political consciousness of our heteronomous days. Well affirmed as a principle, unity “transforms all the problems facing Africa” (p. 275), be they on the economic, industrial or scientific levels.

Let's conclude. At a time of large continental groups, will Africa remain an island cut off from all ports? Will it be the dead arm of a river which, after watering fertile regions, ends up drying up in the desert? A great African, A Diop, asks, without firing sarcasm: “Who will take in hand the destiny of Africa? The new Africa, in the configuration of the "United States of Black Africa" will certainly be born. But it will be the work of those who have understood that its birth will go through four levers of control: Unity, Organization, Research and Education.

The great merit of Kabongo Malu is to have understood better than anyone else that the major challenge for Africa, through the African Renaissance as a paradigm and praxis, is to get Black Africa and its diaspora out of underdevelopment, of " long night ". It will be a long-term work requiring Unitarism, Conversion of mentalities, Cultural good in our history from its pharaonic matrix. Besides, wait and see! And let's not forget with E. Morin that "the history exalted by the West is coming to an end, not because there will be nothing left to invent, but because everything has to be reinvented to save humanity from the risk of annihilation".

By Ernest Bula Kalekangudu

Emmanuel Kabongo Malu, L’Afrique appartiendra-t-elle aux Africains en 2063 ? Actualité du Plaidoyer de Cheikh Anta Diop pour les Etats-Unis D’Afrique Noire, PUA, AFROBOOTS, MUNICH, KINSHASA, PARIS, 2023, 312 P.

*This article has been translated from French into English by Marcus Boni Teiga